Climbing Vines: An Essay on Sustainability and Social Change

Disclaimer: Evidence for this piece was last updated on April 10, 2025. Following shifts within the political landscape may be inaccurately reflected in the presented data.

A seven-hour layover changed my perspective on a lot of things.

It’s an uncommon claim to make, but it’s true. Last summer, in May, 2024, my family and I were traveling for the break. We had a layover in Seattle and decided to explore during the time available to us. As I was daydreaming, my vision blurring into flashes of pale concrete and elevated highway exits, a rare sight snapped my focus back into reality.

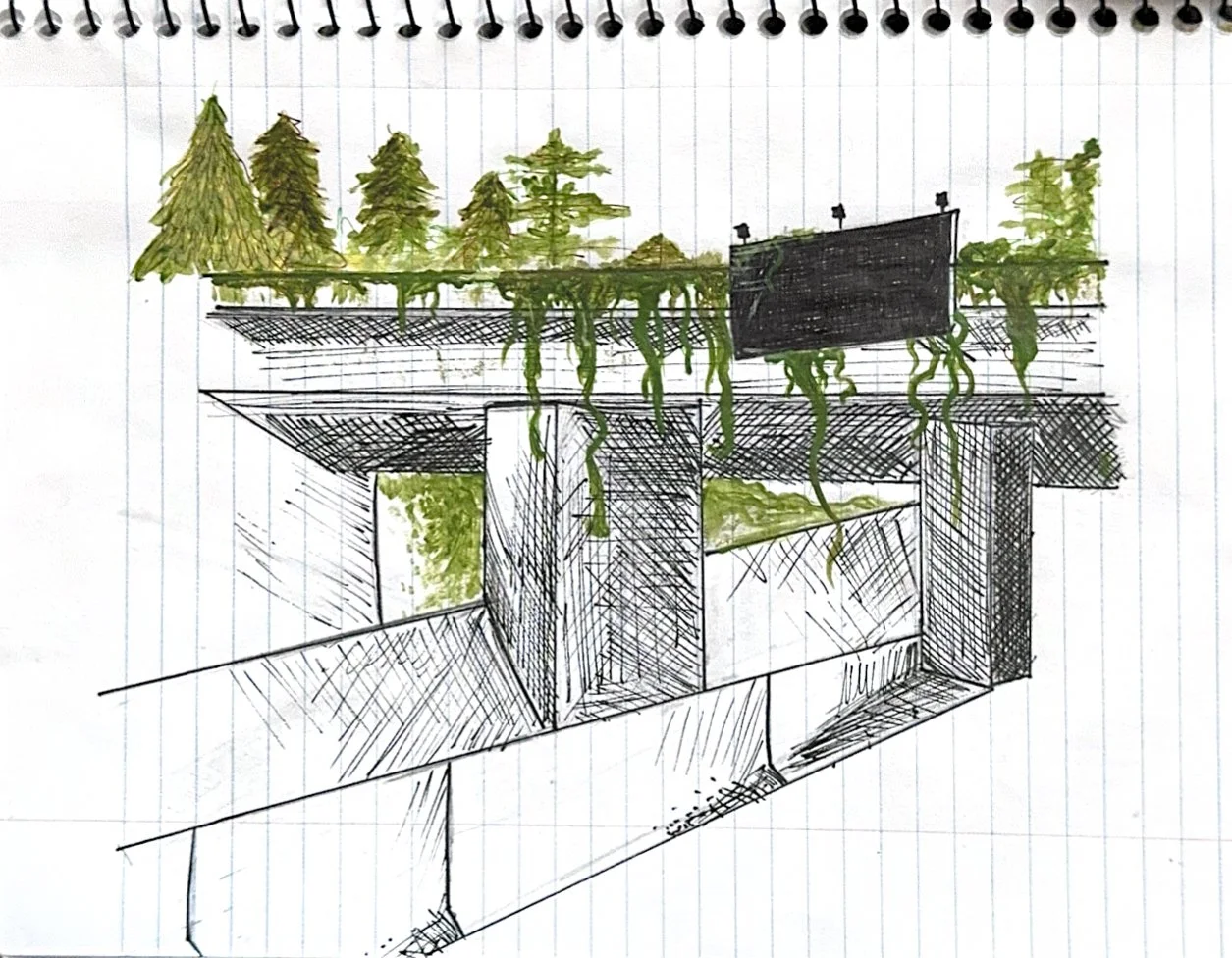

Reimagination: highway in Seattle, WA. May 18, 2024.

Nature.

Vines tangled around monitor frames, dangling off of highway bridges and spilling into the shoulders of the road to nearly stretch under the hundreds of wheels speeding by. Exit bridges criss-crossed around trees and alongside mossy rock faces. Pure concrete looked peculiar against the infrastructure integrated with foliage and soil-stains.

It was just … nature. Kept in mind, planned around, welcomed as it was. It was beautiful — sort of harmonious, preserving the existence of the world before humans changed it and accepting how the world wanted to take back the space it once owned.

And it was sad. Because it shocked me.

The sight of something green — without the artificial touch of a modernist urban planner — was so new I could hardly believe my eyes. My amazement stayed with me, almost dulling my other senses the same way the crisp air numbed my cheeks. Even after I was long gone, shock transformed into curiosity, poking at me until I reached a sense of satisfaction. It came in the form of a question:

Why, exactly, is the preservation of nature so important in urban spaces?

I’m a sustainability studies student here at UT Austin; I already understand and appreciate the value of environmental conservation. Urban ecological integration, however, is not my niche.

But when 76% of low-income communities of color live in nature-deprived areas, I am compelled to wonder about broader implications — how do issues of social equity and ecological exposure interact?

While these areas of thought seem distinct, considerably distanced on a complex spectrum, my educational experience has taught me the importance of examining relationships which may not be immediately visible. It is easy to take for granted the chance to visit green spaces — a park, a hiking trail, a community garden. If we are fortunate enough, these areas, so simple and natural to anticipate, are a regular decoration for our everyday lives. And yet, they help us breathe, they give us space to relax, they provide resources for us to stay nourished. The very ability to engage with environmental spaces has wider impacts of which we may be otherwise unaware.

We have an obligation to look out across that radius. To examine our privilege (or lack thereof) and where it occurs — across an interstate, within a gated community, or even miles away from where we call home. What is the point of building highways around old-growth trees? Why do public-access food forests matter? Most importantly: Who benefits, anyway?

The urban environment is so much more than what we have built. Ecology is so much more than what we may consider wild and separate. Generally, there is so much more.

As I further explore my interests along the intersection of food, justice and the environment, I’ve learned there are connections everywhere.

Like vines climbing up a highway barrier, they’re merely waiting to show themselves.

Transporting Inequity: Highway Systems and the Harms of Displacement

Evidently, transportation plays a fairly significant role in such a discussion. And transportation has complicated legacies.

Here in Austin, everyone knows about Interstate 35. Not everyone knows about its history.

Built through the implementation of Austin’s 1928 City Plan, I-35 became a tool for segregation. Justified by the federal interstate program, the Texas Highway Department (now the Texas Department of Transportation, TxDOT) demolished Black-owned homes and businesses in Austin’s “urban core.” Residents lost their land under premises of eminent domain, were unfairly compensated and then found themselves forced out and away from their neighborhoods. Thus, a majority-Black population was displaced to the underdeveloped and underserved neighborhoods of East Austin. The impacts of Austin’s East/West divide compounded with time and across generations, perpetuated by rezoning, gentrification and government neglect. There are lasting implications of a red line (read: highway) through this city.

These trends in human geography, with concentrations of marginalized ethnic groups in disinvested regions, have been disproportionately driven by the “need” for expansive transportation. As such, these communities are disproportionately impacted by the additional harms caused by transportation.

The externalities of I-35 are shared by multiple other facets of the highway system: historically, the siting of these routes has unfairly exposed low-income and marginalized communities to air, water and noise pollution. And, when lacking effective tree coverage, concrete and pavement absorb excess heat to create what are termed “heat islands” (urban areas in which temperatures are significantly higher relative to outlying areas). When people are forced to breathe smog, drink unclean water, tolerate unyieldingly loud nights and be subjected to extreme temperatures, they are far more prone to negative health outcomes.

Our current transportation system creates profound harms for the environment. Those environmental harms create profound inequities for exposed communities. This cycle is one of environmental racism (wherein low-income, racialized neighborhoods are disproportionately at risk of pollutants and climate change — and are often treated as dumping grounds for environmental polluters). Systemic policies and practices only serve to perpetuate this issue.

And bureaucratic, corporate interests have been getting in the way of change.

Intended to combat the environmental harms caused by federal agencies, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was signed into law in 1970. This act requires agencies to conduct assessments and release information about the environmental impacts of a project, as well as provide opportunities for the public to raise concerns and offer their considerations. The catch, however, is no one is required to do anything. NEPA is not designed to stop projects from being implemented, no matter the harm caused — meaning organizations and agencies can release their reports, pretend to care about civilian concerns and proceed with their plans anyway.

With the projected expansion of I-35, this lack of oversight is especially concerning. TxDOT released a final impact report claiming the overall level of driving, emissions and pollution levels would remain as they do in the status quo (in fact arguing some of these levels would decrease), despite the addition of four lanes to the highway. Not only are these claims entirely unfounded, but there is barely any legislative boundary to what TxDOT is allowed to report. And under new legislation, states are allowed to play judge, jury and executioner — one part of TxDOT conducted their environmental review, and another part signed off. Such decisions are bound to have major implications for the populations already disadvantaged by the transportation system.

Agency over such projects is concentrated in the hands of the influential. And the burden has repeatedly been borne by those who go unheard.

So — how do we lend a voice to the communities otherwise quieted?

Reimagination: highway in Seattle, WA. May 18, 2024.

Amplifying Voices with Environmental Justice

Put simply, environmental justice is a process. It works to ensure environmental protections and benefits extend to everyone, regardless of ethnicity or income. When environmental injustice is shaped by the persisting legacies of racism and inequality, the approach to equity cannot be a one-and-done solution. Harms are complex and compound over time. The harms unique to our transportation system are equally multifaceted — though the environment can play a key role in addressing some of them.

Despite the existing loopholes in federal legislation, the Environmental Protection Agency implemented a strategic plan to promote environmental justice in the long-term. The four essential principles were simple enough: follow science, follow the law, be transparent and advance equity. Under these principles were multiple goals, ranging from “tackling the climate crisis” to ensuring clean-water infrastructure for underserved communities. A swath of transportation-specific regulations were also outlined for all-duty vehicles, school buses, port vessels, vehicle-electrification, aircraft, rail and more. These goals were also set to extend to decreasing fuel consumption and incentivizing the use of renewable fuels.

This plan was set to run from 2022–2026. Any of its official government information is no longer open-access, signifying the cancellation of these initiatives.

These goals seemed promising — but even so, they were all about development.

I’m thinking of Washington again. How the concrete was barely visible behind curtains of vegetation. And how, in the summer, the weather was still cool.

Of course, there are other geographic and political factors at play to influence the climate. But that doesn’t mean the ecology had no impact.

Interestingly enough, the first highway cap park in the world was actually in Seattle — opened in 1976 over Interstate 5, Freeway Park was intended to connect community members despite the physical divide created by this interstate. Parks like this one have been praised for improving (and increasing) access to green spaces. As such, the benefits associated with urban greenery can, too, be associated with the concentrated communities of color who are otherwise disconnected from nature spaces.

But these benefits extend further. Rooftop gardens and urban forests are well-known concepts, but their overarching effect on climate regulation is less familiar to most. It’s fascinating — urban ecology has the potential to sequester carbon at volumes 3–5 times higher than natural soils. Granted, this statistic could merely be true because urban areas have higher atmospheric carbon concentrations. However, equitable vegetation cover also hosts significant contributions to mitigating the heat-island effect. Both by minimizing the surface area which absorbs heat and by reducing carbon, temperatures decrease significantly.

So, pollution can be circumvented. Excess heat can be avoided. People can visit a park. How is that justice?

Low-income communities of color are primarily at risk due to the intensity of pollution, emissions and heat islands resulting from the highway infrastructure bordering their neighborhoods. They often lack the ability to engage with their environment in a meaningful, healing manner. These communities have been voicing their concerns and their strife for decades.

Listening to them and effecting the change they have been asking for, mitigating that pollution and that heat while bridging their disconnect, means an overall decrease in environmental harm — and a reprieve for those most impacted.

Cultivating Colonialism: The Appropriation of Community Agriculture

Vines don’t just climb around highway supports; they weave around stakes and chicken wire, too.

Urban vegetation isn’t necessarily limited to overtaking man-made structures. Rather, there can be cooperation between people and planet; and typically, when people think of urban ecology, community gardens are the default image.

Also colloquially termed “urban ag,” community agriculture prioritizes local involvement. Farmers, gardeners, and volunteers donate and cultivate produce — typically, the space is available for everyone to use as they need and contribute what they can. Urban ag engages the people it serves to provide resources in a sustainable manner.

While well-intentioned, such agriculture as it stands today does have a dark side.

To contextualize the status quo of urban food production, we need to understand its history. After the abolition of slavery in the United States, many Black individuals sought to acquire wealth through land ownership. Despite barriers established in an incredibly prejudiced society, 5.1 million Black farmers managed to acquire over 16 million acres of land in 1920. However, the enforcement of Jim Crow laws and national industrialization pushed many Black communities out of the South, contributing to a 95% decline in Black farmers nationwide. Today, there are fewer than 50,000 Black farmers in the States.

The trend across our nation’s history is such: with discrimination comes displacement, and with displacement comes discrimination. Much like in Austin with I-35, there are profound nationwide patterns of racial residential segregation. Further, redlined neighborhoods are especially subject to disinvestment due to a phenomenon known as retail redlining: supermarkets and grocery retailers refuse to set up base in these communities because they haven’t been developed (which is interpreted as a risk for development). Such decisions perpetuate a cycle of decline, thus mitigating the access to healthy food in these already-marginalized communities.

Urban agriculture has been used by these very groups as a form of resistance. For decades, Black folks have established community farms and gardens, providing fresh food for their neighbors disproportionately at risk of negative health outcomes. Engaging in urban ag as a means of self-determination and political agency serves to empower these communities otherwise disappointed by their governing body and available resources.

The problem is when people view such expressions of power and then decide to play the savior.

It’s happened before: When settlers developed their lifestyles on new land, they failed to recognize Indigenous cultivation as legitimate and viable. Thus began the narrative of the “starving Native American,” further justifying the “civilization” of Indigenous Peoples. The communities which taught settlers how to survive were instantly discredited once cultivation practices were adopted for colonial expansion.

Even now, traditional growing practices — and their histories — are being disregarded in an evolving dynamic. Urban and community agriculture has become exclusionary. Privileged actors have begun to dominate the agricultural space in communities of color, approaching urban ag as “trendy,” “charitable” and “photogenic.” Not only are the origins of urban ag overlooked and overtaken, but so is its inherent purpose. Dispossession and displacement are very real impacts which people of color face when predominantly-white actors attempt to “help” or “improve” community access to food. This approach to “fixing” the community is easily perceived as colonial; and the integration of urban gardens by outside actors drives a clear transition into gentrification.

Urban ag by disadvantaged communities of color is further overshadowed — these initiatives receive significantly less funding, land access and political support than white-led programs. For Black and Brown communities, there is physical exclusion from the spheres of land-ownership, agriculture and food access.

Community agriculture, in this sense, is not conducive to the community. So what is?

On that highway, infrastructure disrupted what the Earth already held.

The vines took it back.

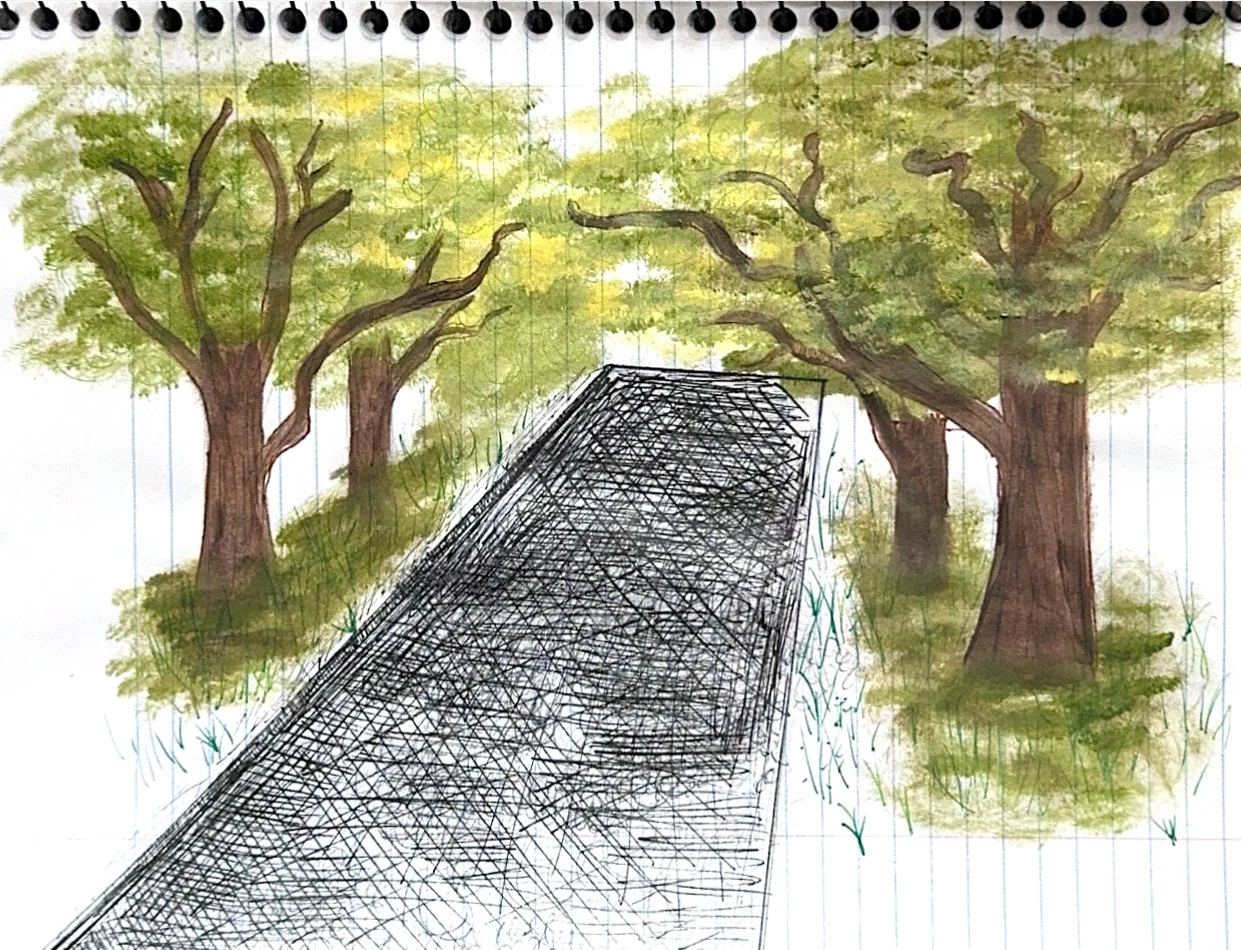

Reimagination: trees along 24th St., Austin, TX. April 3, 2025.

Returning Resistance through Food Justice

Food justice closely addresses the systemic drivers of food inequity in marginalized communities. Understanding how the global food system is rooted in empirical discrimination and racial capitalism, food justice works with and for the peoples disproportionately impacted.

People frequently organize under the banner of “food justice” — but whether they actually practice it is a different matter altogether. With community agriculture, the line can be difficult to walk.

For example, urban ag in a predominantly-Black neighborhood by non-community actors working under their own independent agenda (especially under the mission to “fix” problems like food insecurity) is not food justice. Rather, it ignores what the neighborhood may need and/or want, places the gardeners on a pedestal and fails to empower the community members to systemically address their concerns. In doing so, such an initiative encourages dependency — and food justice ideally promotes sovereignty (the right to engage with and define one’s own food system to guarantee access to healthy and culturally-appropriate foods).

That’s not to say community agriculture is ineffective, nor is it impossible to use as a food justice tool. It just needs to be used correctly.

The most important component of justice is community empowerment. As food inequities are driven by racial and economic disparities, food justice works to bridge the gaps and mobilize these marginalized groups. Community gardens, as initially used, can be an effective means of resistance to oppressive social structures. More so, they are educational, skill-building and health-promoting. The integration of a community-grown food system allows for people to learn about sustainable cultivation and healthy eating; and localized ecological integration (as previously established) mitigates climate extremities which contribute to other negative health outcomes. Urban food production also supports the emergence of alternative economic spaces, reframing local economies to financially empower these communities. As a result, food inaccess because of [in]affordability is circumvented.

There are plenty of other approaches to and implementations of food justice. Whether to uplift localities or empower larger demographics, what matters is the mobilization of community members and the advocacy for unique solutions to their unique challenges. Minimizing barriers to food access, re-establishing traditional foodways, cultivating political literacy and civic engagement — no matter what it may be, the approach to food justice must revolve around an understanding of the food system’s foundations in exploitation and discrimination.

Urban ecology can further justice for the communities in need of it, so long as its integration and its function are determined by those very communities — just as they were at their beginnings.

Projections for the Future: Activism in the Wake of Indifference

I would be remiss to neglect the shifting climate which surrounds us all. In a very literal sense, yes, but also in a political one.

The preservation of our environment and the well-being of marginalized communities have become increasingly polarized issues. Ideology aside, the fact remains that people and planet are repeatedly overlooked in favor of profit.

These are the three tenets of sustainability. People, Planet, Profit — Equity, Environment, Economy. Regardless of the appointed labels, it’s clear how the decisions being made in positions of power are skewing interests further and further out of balance. As we adjust to a new phase of national leadership, there are genuine concerns about choices being (and soon to be) made.

This Trump administration is one teeming with fossil-fuel supporters. Coal, oil and gas have been praised in the name of prosperity, advocated for in the name of economic efficiency and prioritized in the name of protectionism. Science has been consistently denied, renewables consistently discredited, agreements consistently threatened for the sake of an agenda which ignores the people who need to be listened to the most.

Lee Zeldin, the new head of the Environmental Protection Agency, has declared his intent to further roll back ecological protections which have already been under scrutiny and threat. $20 billion worth of grants under the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund have been stripped from the nonprofit organizations battling our ever-increasing climate impact. Environmental justice itself is set to be eliminated in all forms within the operations of the federal government.

We no longer seem to have an environmental protection agency. I worry that soon, I will grow even more shocked to see something green in a built setting.

Some argue how the influence of consumers and corporations will encourage further action to benefit the climate and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. How decisions made by our international neighbors — and our position in the global sphere — will provide enough incentive to keep our current progress on track.

But again, a key tenet is overlooked in those reassurances. I want to see a discussion of equity.

It won’t come from the corporations. Nor the wealthy interests.

Justice is fundamentally by and for the people. No matter the governing body, and no matter the national standard.

In a volatile political climate, our attention should be here: in our neighborhoods, our communities, our homes. There are real, tangible impacts from advocacy and activism for the issues which matter most — the environmental pollution in communities of color, the exposure to extreme temperatures for lower-income individuals, the inadequate access to healthy foods in Black and Brown neighborhoods, the ever-rising concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

These issues are not mutually exclusive. The protection of the environment, the prioritization of equity and the balance of economic efficiency are not impossible to intersect.

Rather than forcing the Earth away and filling the space with a built marker of our presence, it’s time we integrate it back — into our structures, our communities and our considerations. There are connections to be discovered and gaps to be bridged together. People can push for the change they need.

The inclusion of ecology in our urbanizing communities has led to at least one conclusion. And I, frankly, am pleased with the answer to my long-pondered question:

Action for the planet can equate to justice for its people.

We’re merely waiting for someone to stop clearing away the vines.