Recycling to Ease your ‘Eco-Guilt’

Thinking about every piece of trash one has ever produced could be very overwhelming. A single piece of waste used once, like a coffee cup grabbed in a rush, might outlast us all. It is unpleasant but not difficult to imagine, for everyone has heard the macabre factoid: “a piece of plastic waste you consume will exist on this Earth for thousands of years.”

I think about all of this fairly often. It contributes to a general sense of "eco-guilt" or "eco-shame," characterized by an inability to throw things away freely without a second thought. But how much thought is reasonable to give such throw-away tasks? Should I be so hyper-aware of the permanence of my trash?

Research featured in Ecopsychology indicates that eco-guilt, felt about one's environmental impact, can motivate eco-friendly behavior. The study suggests such feelings can lead to increased engagement in sustainable practices, as people naturally aim to align their actions with their values.

We learn object permanence as children when we realize that things exist even when unseen. However, we seem to want to forget about the permanence of our trash, literally burying it as is evidenced by our landfills, which attempt to masquerade themselves as hills under mounds of earth.

I’ve only recently become so overly cognizant of my trash when we stopped recycling at home. After my partner once chased down a recycling truck and was told our bin didn’t get picked up because our recyclables were bagged (even in recyclable bags, which aren’t accepted), we replaced it with a trash bin. It felt wrong: unsustainable, irresponsible. Further, I’ve felt throughout my life that recycling was the only way to counter the aforementioned sense of anxiety at producing waste. I did not realize recycling had been my way of managing waste-related anxiety until this point. What started as my mourning of a personal habit disrupted became a deeper reckoning with recycling as a greater concept, a reckoning that followed my personal history with recycling across geographies.

I decided to keep recycling anyway, and started taking big collections of recyclables to the large dumpster behind my partner’s workplace. Collecting and transporting them myself forced me to learn more about the rules and regulations of recycling, taking me from casual curbside recycling to making trips to Austin’s Recycle and Reuse Drop-off Center.

Most rules are either intuitive, or are printed on your recycling bins and the packages of the very things you are disposing of. The process only becomes tedious when you start to rinse containers, remove labels and question whether or not ambiguous items should/could be recycled. Fundamentally, it doesn’t feel intuitive to clean something before throwing it away.

Some people thus might just find it easier to throw something away rather than to navigate the complexities of recycling, spending equal energy on the disposal of a piece of trash as they did on its casual consumption.

The psychology makes sense: it’s unsettling to think a plastic water bottle used for minutes might exist for millennia. Confronting that reality creates cognitive dissonance. I’m no psychologist, but it is stressful to be confronted with the 1,000-year life cycle of a plastic water bottle that took you minutes to drink.

Lots of materials, like styrofoam, have recycling symbols on them. You might assume that such material is recyclable, but you would be wrong. Further, there are no universal recycling laws.

This is why, during the same approximate adolescent period of our lives that we learn about object permanence, most children also learn the mantra “reduce, reuse, and recycle”: the hierarchy of waste.

It is a hierarchy, represented as a pyramid, that asserts that to avoid the pitfalls of recycling, we should just consume less and thus reduce the amount of material to consider throwing away or recycling. Otherwise, we should repurpose things, or reuse them multiple times. It is only then that you’d even have to worry about rinsing containers and removing labels.

I think I’m especially aware of the life cycle of my recycling — to the point of thinking about it before I produce it —- because I grew up in a country that did not recycle. I lived in Kuwait during my formative years, and despite the country being one of the world’s wealthiest countries and having the wherewithal to recycle, there’s no recycling service.

The United States has the wherewithal and only recycles to a certain degree, dishearteningly; only 5% of U.S. plastic waste got properly recycled in 2021, according to environmental group Beyond Plastics. It seems most people regardless of nationality are lackadaisical about recycling and have largely taken it for granted. Further, my anxiety about this is bolstered by an idea in my head, that: this sense of hyper-awareness is merely me being environmentally conscious and that I should not try and fight or stop being mindful of my waste.

So, I decided to take a trip to the Recycle and Reuse Drop-off Center. Despite Austin’s size and population, the center is Austin’s one and only location, and further, one can drop off their recyclables by “appointment only.” Upon further thought, it seemed only fair that the people working there would like to know the sort of recycling they’ll be receiving and processing beforehand. I brought with me a fairly small amount of recyclables, mostly what the center classifies as “mixed” household waste, like bottles and cans.

When making an appointment, and selecting what you plan on dropping off, options include hazardous waste, like paint, batteries, or electronics. While there, I noticed groups there apparently on business, dumping large collections of cardboard boxes. The center receives drop-offs of widely varying sizes, and given the slight inconvenience of its single location and the required ‘appointment’ system, the center appears to serve more businesses and organizations handling large loads than individuals dropping off their smaller collections on a weekly basis.

The other half of this center’s name, “Reuse,” refers to its less apparent function of reusing materials people drop off.

In arriving, I drove up the road populated with other industrial warehouses and factories, and was greeted by a man at a booth not unlike a ticket booth or a toll station. We confirmed my appointment and he asked what sort of stuff I brought to drop off. He then explained that most of what I would drop off into the mixed recycling bins would be picked through by the unhoused people who frequently visit.

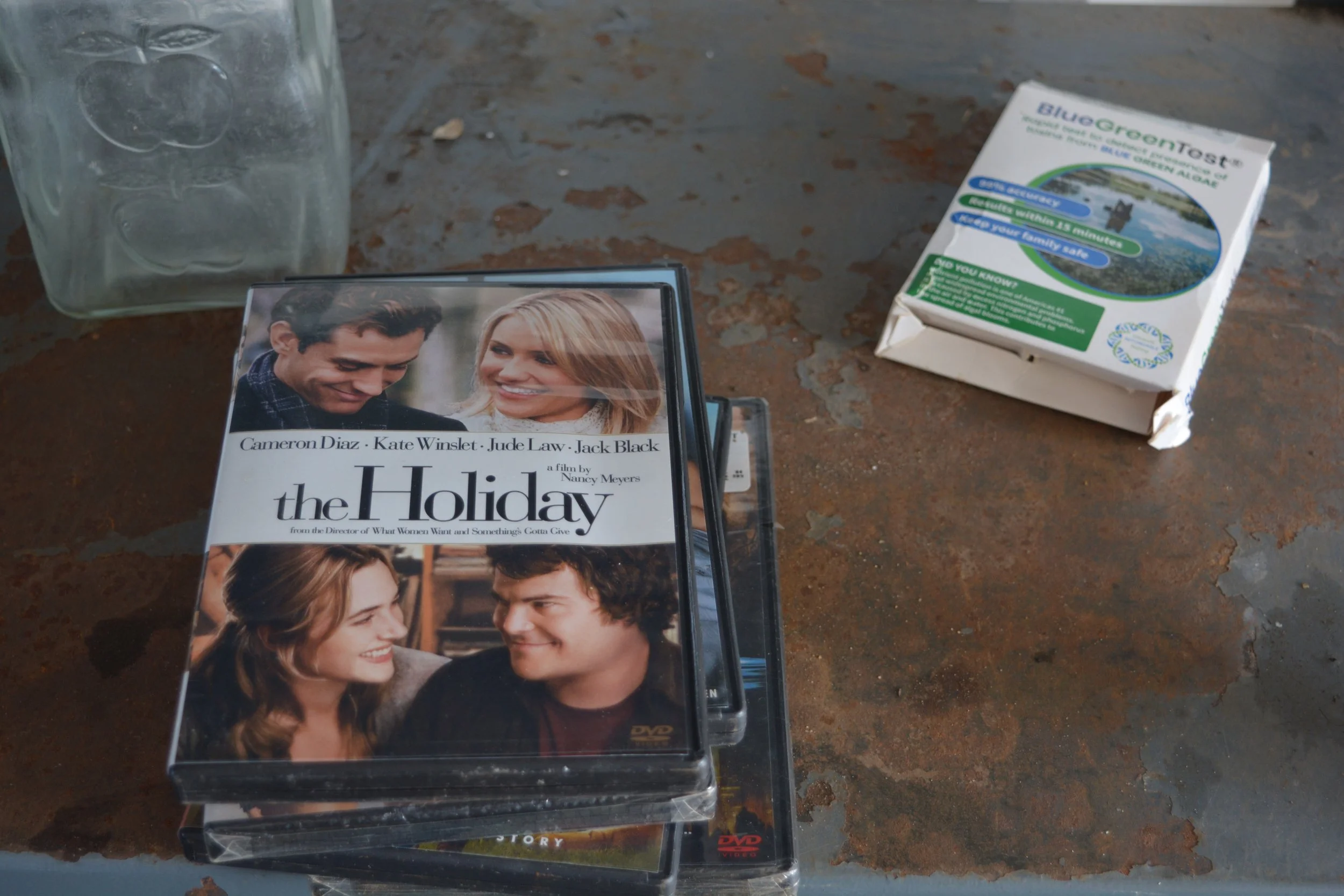

In the same vein, in the back of the facility, there was a very small shed branded the “re-store.” Inside, there was a very sparse and odd collection of things, both seemingly new and used but useful. It looked more like a standard thrift store fare except for the few items with some sort of utility like paint and pesticides, and this Cameron Diaz DVD.

For a city Austin’s size, I was surprised at how small the operation seemed. But, this is merely the public drop-off center –– the materials that people put in blue bins get trucked off to two, much larger facilities.

At the drop-off centre, there are a few medium-sized bins (smaller than a standard dumpster) for mixed recycling, then a single, larger bin for cardboard and other larger materials. There were also several large dumpsters, these two pictured and some more at the back, all full of trash.

When I think about my history with recycling, from my childhood in Kuwait without recycling, to chasing recycling trucks down Austin streets: I realize it's less about perfecting my environmental practices and more about me coming to terms with the permanence of my trash. The plastic coffee cup I use today might outlive not just me but generations beyond me. This realization sits with me, sometimes as a burden of guilt but also as a sense of awareness that shapes my choices.

My visit to Austin's modest Recycle and Reuse Drop-off Center was both enlightening and humbling. It seemed to embody the public’s imperfect but necessary attempts to address waste. It wasn't the grand operation I'd imagined, but environmental stewardship can happen in small, imperfect spaces, one appointment at a time.

I don't claim to have solved my eco-anxiety or perfected my relationship with consumption. But, I have come to value this tension. It keeps me honest about the permanence of my choices without paralyzing me with guilt.

Here, on UT’s campus, I notice bins filling up with trash and recycling between classes, and I wonder about the stories behind each discarded bottle or can, not with judgment but with curiosity about our collective relationship with the permanent impact of the things we use and discard.

The lesson I've learned isn't about recycling techniques or waste management systems but about presence: being present enough to consider the lifespan of something before and after it passes through your hands. This awareness, let alone just my own, doesn't solve the larger environmental challenges we all face, but it connects me to something larger than my momentary needs. It reminds me that in a world of disposable things, our choices have staying power. Awareness alone could be a good place to start.